David beats Goliath or How little brother beat big brother in a benchmark battle.

It's all about system design and these slim form factors put system design at a premium especially with Core-M.

http://www.anandtech.com/show/9117/analyzing-intel-core-m-performance

The story of How 5y10 beat 5y71 and the Designers Dilemma.

It's a long detailed story but well worth the read for the technically inclined. You will learn many lessons about benchmarks, performance, and system design or may become more aware of not so obvious facts or perhaps just perplexed.

The short version is that due to system design, specifically cooling and thermal design choices, the lowest member of the Core-M family bests the top end of the Core-M family in a number of benchmarks of commercially released products. Sometimes it pays to hurry up and get done while other times a more measured steady approach takes the prize.

Imagine if we could predict the duration of a code stream and pick the right strategy for executing it. If it's short punch it and get idle as soon as possible to cool off. If it's long, we better pace ourselves to last the distance. I believe one day we will get there. It would be no more challenging than what Tegra did with the K1 Denver core.

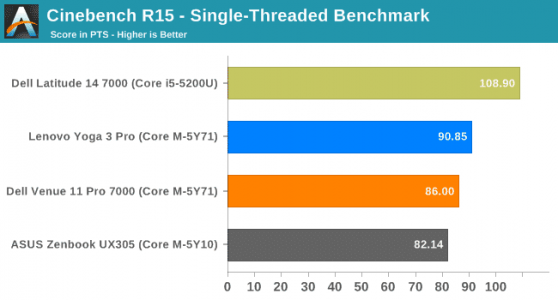

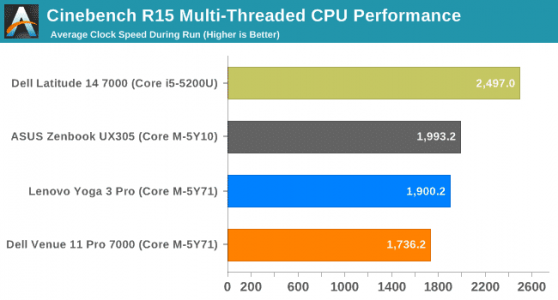

Little brother 5y10 comes in last on single threaded Cinebench

http://www.anandtech.com/show/9117/analyzing-intel-core-m-performance/4

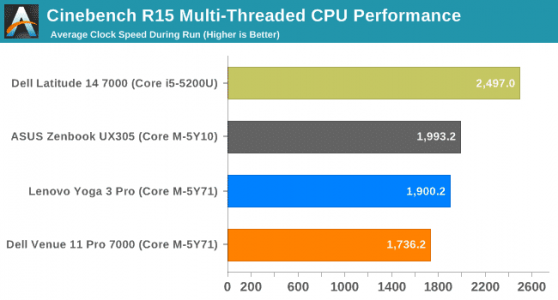

but he comes right back and scores an upset on the multi threaded Cinebench

Just ignore that Dell Latitude he's a ringer (Core i5) brought in to show who's still boss.

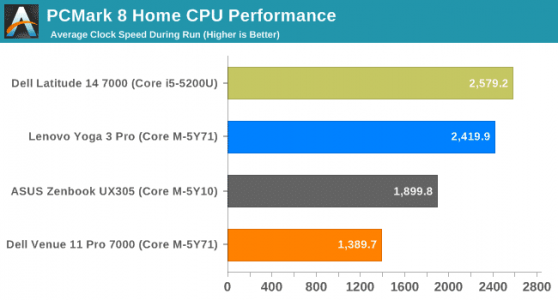

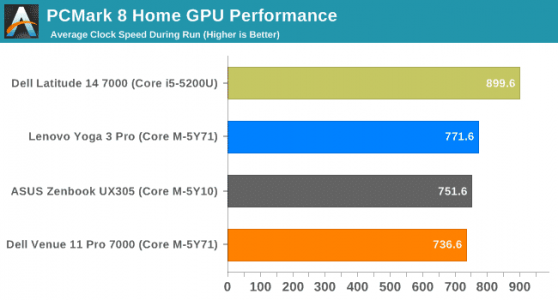

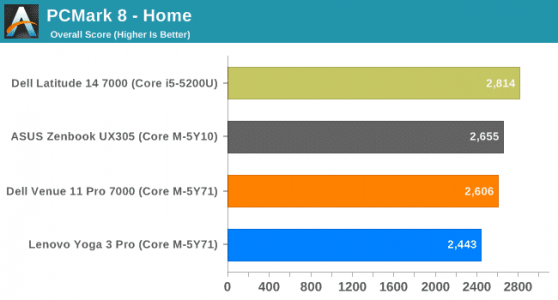

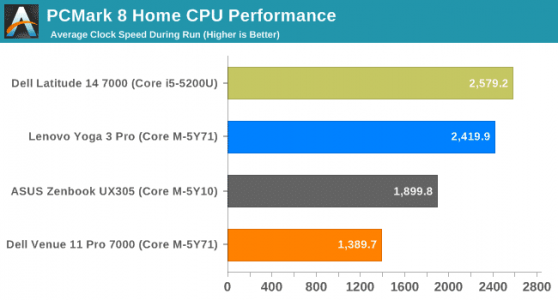

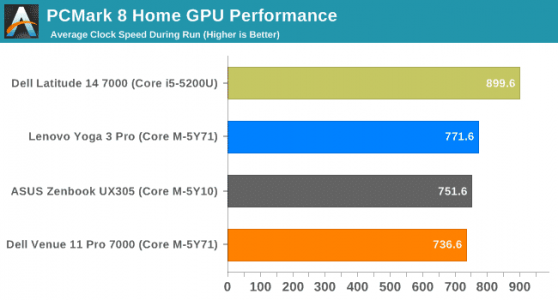

Now things get really interesting we have a multi part test with CPU, GPU and Overall scores.

Little bro comes in second on the CPU and the GPU

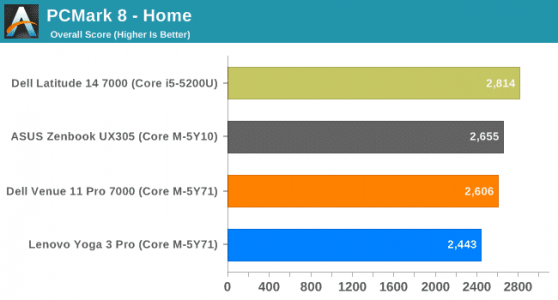

but ... wait for it... wins the Overall

Again just ignore Mr Latitude.

There's much more ... in the article.

http://www.anandtech.com/show/9117/analyzing-intel-core-m-performance

So how did the 5y10 (little bro) beat the 5y71 (big bro) on these benchmarks?

Even more simply put, the System Design. The 5y10's system design allows it to reach a higher temperature and stay in turbo mode longer.

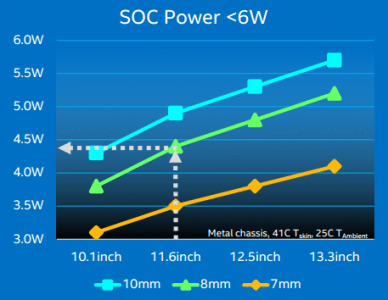

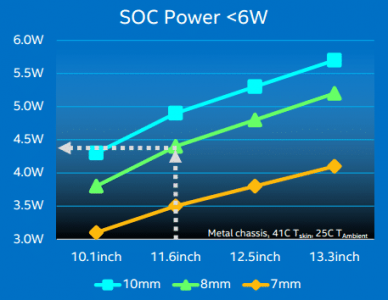

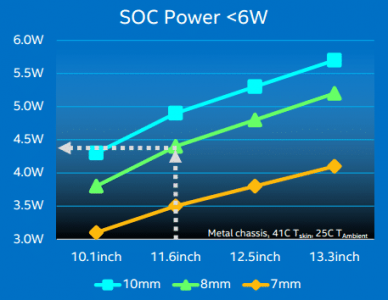

A lot has been made of the metal *styling* of certain devices. News flash, metal conducts heat. Metal casing is an integral part of the system thermal conductivity, you may even call it essential. Back to the Intel chart above, for any given chassis temperature and tablet size and thickness, there was an ideal SoC power to aim for:

It's all about system design and these slim form factors put system design at a premium especially with Core-M.

http://www.anandtech.com/show/9117/analyzing-intel-core-m-performance

The story of How 5y10 beat 5y71 and the Designers Dilemma.

It's a long detailed story but well worth the read for the technically inclined. You will learn many lessons about benchmarks, performance, and system design or may become more aware of not so obvious facts or perhaps just perplexed.

The short version is that due to system design, specifically cooling and thermal design choices, the lowest member of the Core-M family bests the top end of the Core-M family in a number of benchmarks of commercially released products. Sometimes it pays to hurry up and get done while other times a more measured steady approach takes the prize.

Imagine if we could predict the duration of a code stream and pick the right strategy for executing it. If it's short punch it and get idle as soon as possible to cool off. If it's long, we better pace ourselves to last the distance. I believe one day we will get there. It would be no more challenging than what Tegra did with the K1 Denver core.

When Intel put its plans on the table for Core M, it had one primary target that was repeated almost mantra-like to the media through the press: the aim for fanless tablets using the Core architecture. In terms of physical device considerations and the laws of physics themselves, this meant that for any given chassis temperature and tablet size and thickness, there was an ideal SoC power to aim for:

[This one chart explains it all beautifully ... Or does it It does to me.]

It does to me.]

[This one chart explains it all beautifully ... Or does it

Core M is clocked and binned such that an 11.6-inch tablet at 8mm thick will only hit 41°C skin temperature with a 4.5 watt SoC in a fanless design. In Intel's conceptual graph we see that moving thinner to a 7mm chassis has a bigger effect than moving down from 10mm to 8mm, and that the screen dimensions have a near linear response. This graph indicates only for a metal chassis at 41°C under 25°C ambient, but this is part of the OEM dilemma.

When an OEM designs a device for Core M, or any SoC for that matter, they have to consider construction and industrial design as well as overriding performance. The design team has to know the limitations of the hardware, but also has to provide something interesting in that market in order to gain share within the budgets set forth by those that control the beans.

This, broadly speaking, gives the OEM control over several components that are out of the hands of the processor designers. Screen size, thickness, industrial design, and skin temperature all have their limits, and adjusting those knobs opens the door to slower or faster Core M units,

The OEMs' dilemma, for lack of a better phrase, is heat soak causing the SoC to throttle in frequency and performance.

Enough theory lets jump right into the juicy part, we will loop back later for more of the really fun stuff. When an OEM designs a device for Core M, or any SoC for that matter, they have to consider construction and industrial design as well as overriding performance. The design team has to know the limitations of the hardware, but also has to provide something interesting in that market in order to gain share within the budgets set forth by those that control the beans.

This, broadly speaking, gives the OEM control over several components that are out of the hands of the processor designers. Screen size, thickness, industrial design, and skin temperature all have their limits, and adjusting those knobs opens the door to slower or faster Core M units,

The OEMs' dilemma, for lack of a better phrase, is heat soak causing the SoC to throttle in frequency and performance.

Little brother 5y10 comes in last on single threaded Cinebench

http://www.anandtech.com/show/9117/analyzing-intel-core-m-performance/4

but he comes right back and scores an upset on the multi threaded Cinebench

Just ignore that Dell Latitude he's a ringer (Core i5) brought in to show who's still boss.

Now things get really interesting we have a multi part test with CPU, GPU and Overall scores.

Little bro comes in second on the CPU and the GPU

but ... wait for it... wins the Overall

Again just ignore Mr Latitude.

There's much more ... in the article.

http://www.anandtech.com/show/9117/analyzing-intel-core-m-performance

So how did the 5y10 (little bro) beat the 5y71 (big bro) on these benchmarks?

Simply put, if the system with 5Y10 has a higher SoC/skin temperature, it can stay in its turbo mode for longer and can end up outperforming a 5Y71, leading to some of the unusual results we've seen so far

Even more simply put, the System Design. The 5y10's system design allows it to reach a higher temperature and stay in turbo mode longer.

A lot has been made of the metal *styling* of certain devices. News flash, metal conducts heat. Metal casing is an integral part of the system thermal conductivity, you may even call it essential. Back to the Intel chart above, for any given chassis temperature and tablet size and thickness, there was an ideal SoC power to aim for:

Core M is clocked and binned such that an 11.6-inch tablet at 8mm thick will only hit 41°C skin temperature with a 4.5 watt SoC in a fanless design ....

This graph indicates only for a metal chassis at 41°C under 25°C ambient, but this is part of the OEM dilemma.

This graph indicates only for a metal chassis at 41°C under 25°C ambient, but this is part of the OEM dilemma.

Last edited: